News

Trump Threatens to Hit Brazil with 50% Tariffs, Lula Fires Back

WASHINGTON, D.C. – US President Donald Trump has announced new plans for a 50% tariff on all goods imported from Brazil, set to begin on 1 August 2025. The move, made public in a letter Trump posted on Truth Social, has sparked strong criticism from Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Trump’s statement pointed to the prosecution of former President Jair Bolsonaro and what he called restrictions on US social media firms as the main reasons. Lula quickly promised to match the tariffs if they come into effect, setting the stage for a possible trade fight. The dispute has brought fresh attention to Brazil’s courts, its economy, and its connections with China through the BRICS alliance.

Trump, in a direct letter to Lula, blasted Bolsonaro’s ongoing trial, calling it a “witch hunt” and “a disgrace for the world to see.” Bolsonaro, often compared to Trump, is facing charges for trying to overturn the 2022 election and encouraging unrest in Brasília on 8 January 2023.

Trump, drawing comparisons to his cases at home, demanded the trial stop, claiming Bolsonaro “did nothing wrong but speak up for the people.”

Trump also argued that Brazil’s Supreme Court handed out “hundreds of SECRET and UNLAWFUL Censorship Orders” against American social media companies, threatening them with heavy fines and possible bans. He claimed Brazil’s approach to trade left the US with “huge deficits,” even though government data shows America has had a $410 billion surplus with Brazil over the past 15 years.

Trump linked his tariff plan to the BRICS summit in Rio de Janeiro earlier this month, where leaders spoke against rising tariffs, hinting at his trade measures.

This new 50% tariff would be a jump from the 10% rate he set in April and is part of a broader set of trade actions against 22 countries, including Japan and South Korea. But his letter to Brazil is unusual, as it focuses on political and judicial matters, not just trade.

Lula’s Strong Response

Lula dismissed Trump’s remarks, saying Brazil’s courts are independent and the nation “will not be lectured by anyone.” Speaking in Brasília, he said Bolsonaro’s trial is a matter for the judiciary alone. Lula referred to a new Economic Reciprocity Law, passed this year, which allows Brazil to match foreign tariffs. “If Trump hits us with 50%, we’ll do the same,” Lula told Reuters, signalling a tit-for-tat response.

Brazil’s Foreign Ministry called in the US chargé d’affaires twice, first over the embassy’s support for Bolsonaro and again after Trump’s letter. Lula even instructed his team to send Trump’s letter back if it arrives at the presidential office. Finance Minister Fernando Haddad tried to ease the tension, suggesting that talks could help, but Lula stood firm in public.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is one of Brazil’s most well-known politicians. He grew up in a poor family and led the Workers’ Party to national prominence. Lula served as president from 2003 to 2010, running programmes that reduced poverty and made him popular, especially for the Bolsa Família scheme. Yet his time in office faced corruption scandals, like the “Mensalão” vote-buying case in 2005.

After leaving office, Lula became the focus of the “Car Wash” anti-corruption investigation. He was found guilty in 2017 and jailed for over a decade, but claimed he was being targeted to keep him from running again. In 2019, Brazil’s Supreme Court overturned his conviction, citing bias, which allowed him to run in 2022. Lula won that year’s election by less than one per cent.

Brazil’s Corruption and Court Controversies

Lula’s backers say his cancelled conviction shows Brazil’s courts are political, while others say the legal system is broken. The Car Wash probe revealed widespread corruption among politicians and big businesses, but the use of plea deals and leaked messages caused concerns about how the courts were operating. Justice Alexandre de Moraes, involved in Bolsonaro’s prosecution, has faced claims from Bolsonaro’s supporters that he uses the courts to target their side.

Bolsonaro’s allies in the US have tried to pressure Brazil’s court system, saying Moraes issued “secret” orders to social platforms like X, now owned by Elon Musk. In 2024, Moraes even briefly blocked X over misinformation, before lifting the ban with a hefty fine.

These actions added fuel to claims of overreach, though Brazilian law does require platforms to pull content that encourages violence or attacks the democratic order.

Bolsonaro, president from 2019 to 2022, is fighting several court cases. The main charge accuses him of plotting to overturn the 2022 vote, which led to riots on 8 January 2023.

Federal police have also accused him of planning to kill Lula and a Supreme Court judge, charges he denies. He is further barred from running for office until 2030 for spreading false claims about voting machines, and faces probes for selling official gifts and faking a COVID-19 vaccination record.

Lula insists he has no role in Bolsonaro’s legal problems. “No one is above the law,” he said at this year’s BRICS summit, ignoring Trump’s calls to intervene. Some analysts believe Lula benefits from the trial, removing a major rival ahead of the 2026 election.

Trump’s involvement could backfire by making Bolsonaro look reliant on outside help and sparking nationalist support for Lula.

Brazil’s Closer Ties with China and BRICS

Since returning to power, Lula has built closer links with the BRICS group. This club now includes Egypt and Indonesia and has grown in influence. At this year’s Rio summit, Lula pushed for an alternative currency to the US dollar, which Trump has criticised for years.

Trade with BRICS countries has now passed Brazil’s trade with America and Europe combined, with China as Brazil’s biggest customer. This shift means Brazil relies less on the US and could better handle new tariffs.

Trump accused Brazil of backing “anti-American policies” and saw the BRICS summit’s criticism of tariffs as a direct challenge. He threatened another 10% tariff on all BRICS members in response.

Brazil’s economy has struggled since Lula took office again in 2023. The real lost more than 2% against the dollar after Trump’s tariff threats, and key stocks like Embraer and Petrobras fell. Around 47% of people support Lula, though there is frustration about rising crime and slow growth. While social spending remains, his government has found it hard to turn things around. Brazil’s closed economy offers some protection from global risks, but limits foreign investment.

Corruption is still a problem. Supporters praise Lula’s social programmes, but critics point to new scandals among the Workers’ Party and allies. The fallout from the Car Wash probe still weighs on politics, and claims of mismanagement hang over Lula’s third term. Bolsonaro’s supporters, especially among evangelicals, remain vocal. If the courts convict Bolsonaro, it could only make them more determined.

Impact of the Tariff Dispute

The planned tariffs could hit Brazil’s $40 billion exports to America, harming industries like coffee, meat, and textiles, many tied to Bolsonaro’s core supporters. Still, Brazil’s broader trade links, especially with China, may soften the blow. Lula’s tough stance has united the country in a rare show of solidarity, with even critics like O Estado de S. Paulo calling Trump’s plan “a mafia move.”

For Lula, this conflict could be a boost ahead of the 2026 election. By portraying Trump’s tariffs as an attack on Brazil’s independence, Lula has rallied national pride. “If Lula handles this, his re-election chances just went up,” said Oliver Stuenkel, professor at Fundação Getulio Vargas.

Yet Trump’s move might also weaken Bolsonaro’s case by making him look dependent on foreign backers.

The row between the US and Brazil highlights deeper issues of trade, independence, and how much outside powers can influence national politics. Trump’s use of tariffs as a tool to affect Brazil’s legal process has been compared to strong-arm tactics, with MAGA strategist Steve Bannon calling it “a brave new world.”

Lula has promised to fight back and stand up for Brazil, signalling his refusal to give in to international pressure. The risk of a trade war is real, with potential consequences for both economies and the wider relationship between the US and Latin America.

Source: Reuters

Related News:

Trump Raises the Stakes on Canada Trade Dispute While Carney Vactions

News

Vice President JD Vance to Head Anti-Fraud Task Force Targeting California Welfare Abuses

WASHINGTON, D.C. – President Donald Trump is expected to sign an executive order naming Vice President JD Vance as chair of a new White House anti-fraud task force, according to multiple people familiar with the plans.

The task force under JD Vance will focus on alleged welfare abuse and improper payments tied to California and several other states.

The task force has been taking shape for weeks and marks a more public phase of the administration’s campaign against fraud in federal benefit programs. Vance, a former U.S. senator from Ohio who has often criticized large safety-net programs, will lead the effort.

Federal Trade Commission Chairman Andrew Ferguson is expected to serve as vice chair and run day-to-day work, sources said.

Sources briefed on the planning told CBS News the order could be signed as soon as this week. One person described Vance’s role as a signal that the issue sits near the top of the president’s agenda, not just another routine review.

Why JD Vance is headed to California

Republicans have long pointed to California’s large public programs as a risk point for fraud. The task force is expected to look closely at Medi-Cal (California’s Medicaid program), unemployment insurance, pandemic-era relief programs, and child care subsidies.

Audits and reviews in recent years have flagged large amounts of questionable spending, including billions tied to improper claims during and after the COVID-19 period. Vance has also argued publicly that California’s fraud problem is larger than other widely covered cases, including a Minnesota welfare fraud scandal that drew national attention.

“It’s happening in states like Ohio. It’s happening in states like California,” Vance has said when talking about misuse of federal funds.

The task force plans to examine how federal dollars move through California’s social service systems, including eligibility checks and payment controls.

The new task force follows earlier administration steps, including freezes on certain federal funds to states accused of weak oversight. While the group’s mission is nationwide, California has become a main focus. Supporters say tougher audits protect taxpayers and help benefits reach people who qualify.

California officials call it a political attack

California’s Democratic leaders quickly pushed back. State Attorney General Rob Bonta spoke Thursday in Los Angeles, calling the administration’s claims reckless and politically driven.

Bonta said California has been active in fraud cases and has recovered nearly $2.7 billion through criminal and civil actions since 2016. He cited $740 million tied to Medi-Cal matters, $2 billion recovered under the state’s False Claims Act, and $108 million connected to underground economy tax fraud investigations.

“Trump is out there falsely claiming that California is somehow the problem, baselessly claiming that California programs and public servants are perpetrating fraud, when in reality we are the victim of fraud,” Bonta said.

He added that fraud schemes hit states of all political stripes, including Republican-led Texas and Florida, along with Ohio. Bonta also took a shot at Vance’s role, saying the vice president should look closer to home instead of leading what he called an unnecessary political stunt aimed at California.

Concerns about the impact on people who rely on aid

State officials and advocates worry a high-profile federal crackdown could disrupt legitimate benefits, scare off eligible families, or be used to justify bigger policy changes aimed at Democratic-led states. Critics also point to the administration’s past pardons in fraud cases and argue that it undercuts the message of strict enforcement.

The announcement lands in the middle of ongoing tension between the Trump administration and blue states, especially California. Trump has targeted the state on immigration, environmental rules, and other issues, and the new task force fits that pattern of using executive power to increase scrutiny of state-run programs paid for in part with federal funds.

Supporters, including conservative commentators and some budget watchdogs, say the move is overdue. They argue that rising debt and pressure on entitlement spending make tighter controls necessary. They also say putting Vance and Ferguson in visible roles gives the effort more weight than a typical inspector general review.

Skeptics warn that aggressive investigations can create new paperwork hurdles and lead to mistaken benefit cuts, which often hit low-income residents hardest.

As the executive order details roll out, the task force is expected to coordinate with federal agencies that oversee key programs, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the Small Business Administration, and others.

Whether the task force uncovers widespread abuse or runs into court fights is still unknown. For now, the move has revived a familiar argument in American politics: how to balance fraud enforcement, program access, and the federal government’s role in overseeing state-run benefits.

With Vance in the lead role, the effort also puts the vice president front and center on one of the White House’s main domestic priorities, a position that could raise his profile inside the administration and beyond.

Trending News:

Trump Says Iran Should Be Worried U.S. ‘Prepared’ for Iranian Military Action

News

Trump Says Iran Should Be Worried U.S. ‘Prepared’ for Iranian Military Action

WASHINGTON, D.C. – President Donald Trump used a Fox News interview to send a direct warning to Tehran: the United States is ready to answer any Iranian military move. His comments come during a stretch of rising friction in the region, with nuclear talks in Oman only days away. The moment highlights how close diplomacy and conflict now sit.

Fox News correspondent Benjamin Hall discussed the growing U.S.-Iran standoff. Trump said the U.S. is “prepared” if Iran takes military action. He framed that posture around efforts to block Tehran’s nuclear progress and limit Iran’s reach across the region.

The remarks arrive as reports mount of dangerous encounters at sea, including Iranian gunboats trying to board a U.S. oil tanker and U.S. forces intercepting drones.

What’s driving the latest spike in U.S.-Iran tensions

U.S.-Iran relations have slid fast since Trump returned to office, building on years of disputes over Iran’s nuclear program, proxy groups, and ballistic missiles. The temperature climbed last June after U.S. strikes hit Iranian nuclear sites, following Israel’s 12-day campaign against Iran. Iran’s crackdown on protests after that only added fuel to the cycle.

In recent weeks, Iranian vessels have pressed commercial traffic near the Strait of Hormuz. At the same time, U.S. warships have stepped in to stop threats in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea.

Trump has kept up pressure in public, saying Iran must stop moving its nuclear work forward and cut support for groups such as Hezbollah and the Houthis. In one exchange, he pointed to “very big, powerful ships” positioned near Iran. He said he wants diplomacy to work, but won’t hesitate if it fails.

The strategy resembles Trump’s first-term “maximum pressure” approach, but officials now describe it as more urgent. The administration says any agreement must cover nuclear limits, missiles, and proxy networks. Iran has rejected that broader package.

Oman talks: narrow agenda, high stakes

Even with the threats, both sides are still talking. U.S. and Iranian officials are scheduled to meet on Friday in Muscat, Oman. The talks are expected to focus on Iran’s nuclear program and possible sanctions relief.

The meeting location shifted from Istanbul to Oman at Iran’s request. That move also narrowed the agenda to nuclear issues, leaving out wider regional security topics that Washington has pushed.

U.S. envoy Steve Witkoff is expected to attend, and Jared Kushner may also be involved. They are set to meet Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi. Oman has played go-between for years and has hosted past indirect talks.

Trump has said Iran is “seriously talking” with the U.S., but many remain doubtful. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has said progress depends on Iran accepting limits on missiles and proxy ties. Iranian officials say they will only discuss the nuclear file, and only “on an equal footing.”

Trump has also tied the talks to the risk of force, warning that if talks fail, future strikes could be “far worse” than earlier action.

Iran’s playbook: proxies, missiles, and pressure points

Iran often relies on indirect power rather than head-to-head fights. Analysts describe a layered plan meant to raise the cost of any attack. That includes large waves of ballistic missiles and drones, plus proxy activity tied to the “Axis of Resistance” in Lebanon, Yemen, Iraq, and Syria.

Tehran also holds a major economic threat over the region: disruption in the Strait of Hormuz. Iranian officials have said they would respond “with everything we have” if attacked. They have pointed to options like cyberattacks and interference with shipping.

Still, the past year has exposed weaknesses, including gaps revealed during last year’s strikes. That has sparked internal debate inside Iran about whether a more flexible approach could reduce risk. Other voices argue the opposite, that only the threat of a long conflict can hold the U.S. back.

U.S. naval buildup near Iran

The Pentagon has increased forces in the region to back up Trump’s warnings. The USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group is operating in the Arabian Sea, alongside guided-missile ships and aircraft such as F/A-18 Super Hornets and F-35C Lightning IIs.

Other reported assets include the USS Delbert D. Black, USS McFaul, and USS Mitscher near the Strait of Hormuz. Littoral combat ships are also operating in the Persian Gulf, with added air support from bases in Jordan and Qatar.

Satellite imagery has shown expanded activity at sites such as Muwaffaq Salti Air Base. Missile defenses, including THAAD and Patriot systems, are reinforcing protection for U.S. forces and partners. U.S. officials have described the buildup as a large force meant to deter attacks and allow a fast response if needed.

What happens next, and what could go wrong

The next few days could set the tone for months. A deal in Oman could produce a limited nuclear agreement, ease some sanctions, and cool the situation. A breakdown could bring the opposite, with small incidents turning into direct clashes.

Analysts warn the risks are real: a proxy strike could draw U.S. retaliation, or Iran could try to disrupt key shipping lanes. Either outcome could push energy prices higher and shake global markets.

Regional partners such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE could also face attacks, and Israel could be pulled deeper into the conflict. Trump has held off strikes before to leave room for talks, but his latest comments suggest little patience for what he sees as Iranian defiance.

As attention shifts to Muscat, Trump’s Fox News statement stands as both a warning and a show of resolve. The outcome could be a narrow deal or a wider crisis. The stakes include nuclear risk, regional stability, and global security.

Trending News:

Iran’s Supreme Leader Steps Up Threats as Trump Applies Pressure

Hillary Clinton Calls for Transparency, Wants Televised Congressional Hearing

News

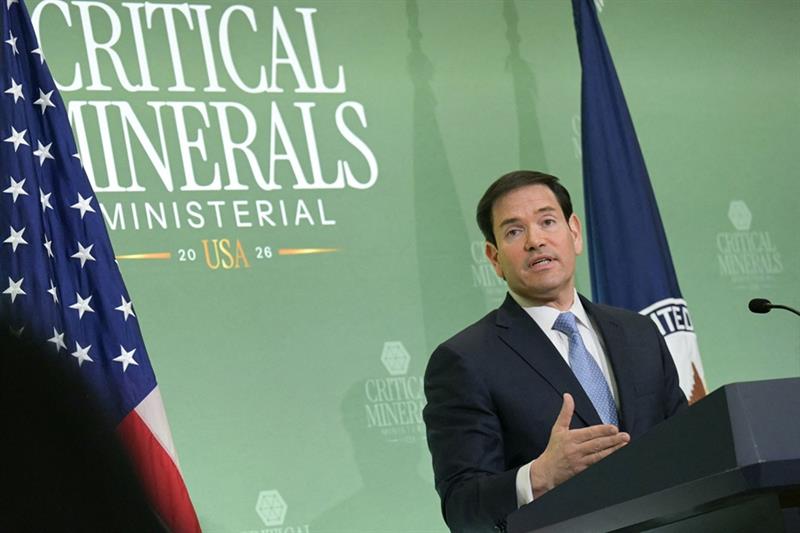

Marco Rubio Accuses Iran of Sponsoring Global Terrorism

WASHINGTON, D.C. – During a press availability at the State Department, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio sharply criticized Iran’s leaders. He accused Tehran of backing terrorist activity across the globe and stressed what he called a deep gap between the clerical government and the Iranian people.

Marco Rubio spoke as the United States weighs possible nuclear talks with Iran. His comments reflected the Trump administration’s tough approach. He argued that Iran, a country with significant wealth and potential, is sending money outward to support proxy forces instead of fixing urgent problems at home. He pointed to issues like water shortages, power problems, and economic strain.

“The Iranian regime is sponsoring terrorism around the world,” Rubio said. He added that Iran’s leaders are “spending all their resources, of what is a rich country, sponsoring terrorism, sponsoring all these proxy groups around the world, exporting as they call it, ‘their revolution.’”

The State Department has labeled Iran a state sponsor of terrorism since 1984. Under Rubio, the department has also moved to renew terrorism designations tied to Iran-aligned militias in Iraq. He has pushed allies to tighten sanctions and has urged partners to designate the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist organization.

Rubio tied Iran’s foreign activities to the hardship many Iranians face. “One of the reasons why the Iranian regime cannot provide the people of Iran the quality of life that they deserve is because they’re spending all their money” on these operations, he said. He pointed to ongoing domestic unrest, including recent protests tied to the economy and government repression, as signs the state can’t meet basic public needs.

A Wide Gap Between Iran’s Leaders and Its People

A key theme in Rubio’s remarks was his effort to separate the Iranian government from the population. “The Iranian people and the Iranian regime are very unalike,” he said. “In essence, what the Iranian people want, this is a culture with a deep history, these are people that the leadership of Iran at the clerical level does not reflect.”

He argued that the difference is unusually large. “I know of no other country where there’s a bigger difference between the people that lead the country and the people who live there,” Rubio said. He described Iran as a society shaped by a long Persian past, and he suggested the current leadership doesn’t represent that identity.

This message matches Rubio’s past public comments, including statements made during his Senate confirmation process. It also fits a broader U.S. strategy, criticize the regime while showing respect for ordinary Iranians. The goal is to build international support for pressure on Tehran without pushing away internal reformers, dissidents, or civil society voices.

Rubio Lays Out Hard Terms for Any Nuclear Talks

Rubio’s remarks came as the U.S. and Iran explore limited engagement. He confirmed reports that Iran asked to change the location of planned talks that were first expected to take place in Turkey. He said the United States is still open to talks, but he made clear that Washington wants more than a narrow nuclear discussion.

“For talks to actually lead to something meaningful, they will have to include certain things,” Rubio said. “That includes the range of their ballistic missiles. That includes their sponsorship of terrorist organizations across the region. That includes the nuclear program. And that includes the treatment of their own people.”

He said he doubts Tehran will accept a broader agenda, since it appears focused on uranium enrichment and related nuclear issues. Rubio added that President Trump prefers diplomacy and peaceful outcomes, but won’t rule out confrontation.

“Our problem with the Iranian regime isn’t simply, obviously it’s predominantly, their desire to acquire nuclear weapons, their sponsorship of terrorism,” Rubio said, “but it’s ultimately the treatment of their own people.”

He also pointed to recent crackdowns, including arrests tied to alleged spying and assisting foreign actors, as more evidence of repression inside Iran.

What Rubio’s Remarks Signal for U.S. Policy

Rubio’s comments reinforce the administration’s maximum pressure approach. That includes targeting Iran’s proxy groups and working with European partners on sanctions. Critics warn that this kind of rhetoric can raise tensions. Supporters say it’s needed to counter Iran’s influence in the Middle East through groups like Hezbollah, Hamas, and armed factions in Iraq.

With frustration inside Iran driven by economic stagnation and human rights concerns, Rubio’s framing may appeal to dissidents and members of the Iranian diaspora who see the clerical system as separate from Iran’s national identity.

Over the next several days, diplomacy will face the same divides Rubio laid out. For now, the message from the Secretary of State is clear, the U.S. views Iran’s rulers not only as a nuclear risk, but also as a sponsor of instability whose priorities clash with what many Iranians want.

Related News:

Iran’s Supreme Leader Steps Up Threats as Trump Applies Pressure

-

Crime1 month ago

Crime1 month agoYouTuber Nick Shirley Exposes BILLIONS of Somali Fraud, Video Goes VIRAL

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoIlhan Omar’s Ties to Convicted Somali Fraudsters Raises Questions

-

China1 week ago

China1 week agoChina-Based Billionaire Singham Allegedly Funding America’s Radical Left

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoWalz Tried to Dodges Blame Over $8 Billion Somali Fraud Scandal

-

Crime2 months ago

Crime2 months agoSomali’s Accused of Bilking Millions From Maine’s Medicaid Program

-

Asia3 months ago

Asia3 months agoAsian Development Bank (ADB) Gets Failing Mark on Transparancy

-

Crime2 months ago

Crime2 months agoMinnesota’s Billion Dollar Fraud Puts Omar and Walz Under the Microscope

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoSouth Asian Regional Significance of Indian PM Modi’s Bhutan Visit