Entertainment

Macrons Sue Candace Owens Over Her Claims Brigitte Has a Penis

DELEWARE – French President Emmanuel Macron and his wife, Brigitte Macron, have filed a major defamation lawsuit against US commentator Candace Owens over her exposé becoming Brigitte in Delaware.

The 218-page filing accuses Owens of running a “campaign of global humiliation,” targeting Brigitte Macron with false claims that she was born male. The suit includes 22 counts covering defamation, false light, and defamation.

The Lawsuit alleges Owens spread these stories to promote her podcast Becoming Brigitte and profit from her large online following: nearly 7 million on X and 4.5 million on YouTube.

Filed on July 23, 2025, the case marks a dramatic moment in a dispute that began on minor internet forums but has grown into a high-profile international legal fight.

The Macrons are now at odds with an outspoken US influencer, forcing a conversation about the limits of free speech, defamation across borders, and the responsibilities of public figures.

While Owens’ lawyers argue the suit is a foreign attempt to silence an American journalist, the Macrons’ aggressive stance and refusal to release certain evidence leave lingering questions and fuel online conspiracies.

Macrons Defamation Claims

According to the lawsuit, Owens began publicly asserting in March 2024 that Brigitte Macron, 72, was born male under the name Jean-Michel Trogneux, who is her brother. These allegations featured prominently in Owens’ eight-part YouTube series Becoming Brigitte, which drew over 2.3 million views.

The series also accused the Macrons of being blood relatives, identity theft, and suggested Emmanuel Macron’s rise to power was the result of a US mind-control plot.

The Macrons claim Owens made these statements knowing they were false, meeting the strict “actual malice” standard in US law, which requires proof that Owens either lied knowingly or acted with reckless disregard for the truth.

The suit describes the harm the couple has faced, including constant public insults and an intrusion into their lives. “Every time the Macrons leave their home, they do so knowing that countless people have heard, and many believe, these vile fabrications,” the complaint says.

Their attorney, Tom Clare of Clare Locke LLP, who previously worked on the Dominion Voting Systems case, calls this suit “a clear-cut case of defamation.” Clare says Owens dismissed solid evidence disproving her story and continued to produce content and merchandise that kept the rumours alive.

Owens’ Response and First Amendment Arguments

Candace Owens has responded with characteristic boldness, dismissing the lawsuit as “goofy” and a shallow publicity move. During a livestream on July 23, she doubled down on her attacks, calling Brigitte Macron the “First Lady man of France.”

Owens’ spokesperson asserts that this is an illegal effort by a foreign government to threaten the First Amendment rights of a US journalist.

“Candace repeatedly requested an interview with Brigitte Macron. Instead of talking, Brigitte tries to bully a reporter into silence. In France, politicians bully the press, but this is America.”

Owens and her legal team look forward to discovery, aiming to question Brigitte Macron under oath and, according to them, get to the truth in court. Owens promises her supporters that she will see the Macrons in court and that the process may reveal even more about the couple.

Owen’s defence is based strongly on her freedom of speech as protected in the US. Public figures like the Macrons have a tough standard to meet. Legal analysts note that because Owens is more of a commentator than a traditional reporter, her work blends opinion and fact, which could work in her favour.

Her team insists that even harsh opinions and speculation are protected by law, given the Macrons’ high profile. Since Owens’ businesses are registered in Delaware, that state’s courts—known for protecting speech—will hear the case.

Experts Weigh in on the Suit and Possible Motives

This lawsuit has divided legal experts. Some believe it’s a weak or even “frivolous” effort designed more to protect the Macrons’ reputation than to win in court. Three top US defamation lawyers, speaking off the record, expressed doubts about whether the Macrons could prove actual malice.

One noted, “Owens can say she relied on French sources, even bad ones, and that could protect her.” Another called the case a “face-saving effort” and argued that the Macrons’ refusal to answer Owens’ requests for comment may hurt their position.

A third expert labelled the case “partially frivolous,” highlighting that the high number of accusations and the demand for damages may be more about intimidation and publicity than about justice.

“Filing in Delaware looks like a stunt,” said the expert, “and could end up helping Owens by giving her a platform during discovery.”

Other lawyers point out that the Macrons have carefully documented their attempts to get retractions from Owens and could prevail if they prove she ignored solid evidence. Since Owens has millions of followers, the couple argues, the personal impact is enormous.

French Lawsuits and Accusations of Overreach

This is not the Macrons’ first attempt to tackle these claims. In France, Brigitte Macron has filed lawsuits against two women, Amandine Roy and Natacha Rey, for spreading similar stories online. In late 2021, the two posted a viral video claiming Brigitte was born male.

A French court convicted them of libel in September 2024, ordering damages, but in July 2025, an appeals court overturned the decision, saying that the pair acted in “good faith.” Brigitte Macron is now appealing that decision to a higher court.

The treatment of Roy and Rey has raised concerns. Natacha Rey, who is reportedly battling cancer, has faced intense legal and police pressure that many see as excessive.

French journalists and activists argue that the Macrons’ focus on these individuals, who have limited resources, threatens press freedom and could discourage open discussion. As one Paris-based journalist put it, “It looks like the Macrons are trying to silence critics rather than address the claims.

Targeting a cancer patient doesn’t help their case, especially when a court already said the allegations were made in good faith.”

Owens has pointed to the appeals court’s ruling as evidence supporting her case, saying the Macrons have switched tactics after failing to win in France. But that leaves out the fact that the ruling focused on good faith, not the truth of the claims.

A Persistent Question: The Missing Proof

A key point in this story is Brigitte Macron’s refusal to release photos, medical documents, or other evidence that could end the rumours for good. The Macrons say they provided Owens with credible information, but have not made it public.

Critics argue that a simple birth certificate or old photos could clear things up quickly. Owens raised this issue again during her recent live stream, and many of her supporters on X agree.

Macron’s lawyers argue public figures should not have to reveal private records just to refute baseless attacks. The lawsuit notes that Brigitte had three children in her first marriage as further proof of her biological sex.

Still, the lack of clear evidence has allowed conspiracy theories to grow even as the couple fights to clear their name in court. The Macrons’ lawsuit situates Owens’ claims within this toxic pattern, accusing her of using gender stereotypes and bigotry for profit and attention.

Owens and her supporters push back, saying she is simply conducting real journalism by investigating these allegations. They point to her use of sources from France, like Natacha Rey, whose claims have not been fully disproven in public.

The recent appeals court ruling in France, they argue, supports their right to discuss unproven stories as long as they act in good faith, which blurs the Macrons’ position as clear-cut victims.

What’s Next: A Case with International Impact

The Delaware case guarantees further debate about the role of social media, the boundaries of speech, and how reputations are protected or damaged worldwide.

If the Macrons win, it could set an example for public figures seeking recourse against false claims made by global influencers. If Owens wins, it would reaffirm broad speech protections for American commentators and raise questions about how far defamation law should go in an era of viral rumours.

Macron’s decision to avoid interviews with Owens or release decisive evidence may be strategic, but it has fed doubts online. At the same time, French authorities’ tough handling of smaller players like Natacha Rey and Amandine Roy has alarmed many about the state of press freedom in France.

As the court proceedings continue, the conflict will highlight the tension between privacy, reputation, and free speech in the age of internet-driven conspiracy theories. The outcome will shape the future of defamation law—on both sides of the Atlantic.

Related News:

Google and Facebook Under Huge Pressure Over User Privacy

Entertainment

Epstein Files Get Broken Down By Alex Jones and Nick Fuentes

In a heated live stream watched by millions, Alex Jones and Nick Fuentes teamed up to talk through the newest release of Jeffrey Epstein records from the U.S. Department of Justice.

The segment aired on Jones’ Infowars platform only days after the first wave of partial disclosures started in late December 2025. Their focus stayed on what the documents suggest about powerful circles, why major outlets have said so little, and which gaps in the record keep driving public anger.

Their broadcast landed in the middle of a tense political moment. After Congress passed the Epstein Files Transparency Act in November 2025, President Donald Trump signed it into law. Soon after, the DOJ began publishing thousands of pages of records, along with photographs and other materials tied to Epstein investigations.

Many pages arrived with heavy redactions, releases came in uneven batches, and reports said more than 5 million pages were still being reviewed. Critics say the slow pace and missing details point to another cover-up, even as the rollout continues into 2026.

A Rare Pairing, Same Complaints

Jones, host of The Alex Jones Show, brought on Nick Fuentes, the far-right streamer behind the America First podcast, for what Jones called a blunt review of the new documents. The two have clashed before, including public disputes about politics and loyalty. On this topic, they sounded aligned. Both criticized the limited disclosures and said influential people were still being protected.

Early in the show, Jones argued the story goes far beyond Epstein himself. He said the files point to influence deals, blackmail, and abuse tied to people with serious power. He also complained that large TV networks were not giving the story constant coverage.

Fuentes agreed and said mainstream outlets have reasons to stay quiet. He claimed the releases mention well-known names, but redactions hide key details. In his view, the public is being fed just enough to calm outrage while shielding the people who matter most.

What the New Records Put Back in the Spotlight

Jones and Fuentes walked through selected items from the December 19, 2025, release and later batches. The materials included undated photos showing Epstein around high-profile figures, including former President Bill Clinton and Ghislaine Maxwell, along with other people whose identities were obscured.

The release also referenced flight logs, emails, and investigative memos tied to travel and communications involving recognizable names, though many lines remained blacked out. The redactions were described as protections for victims or to avoid disrupting active work.

Jones pointed to images and records that show Clinton in social settings with Epstein and Maxwell. He said reports about “Lolita Express” travel have circulated for years, but he argued the newer material strengthens the public record around repeated trips. He also said Epstein’s death, ruled a suicide, continues to raise questions about who gained from his silence.

Fuentes focused on references to business figures, including Leslie Wexner and Leon Black, and the financial ties discussed in relation to Epstein. He framed the case as more than trafficking, calling it a blackmail system built on access to wealthy and connected circles. He pointed to descriptions in the files about properties with cameras and rooms set up for sexual encounters, arguing that the risk powerful people took only makes sense if something larger was going on.

Both also highlighted what they described as an imbalance in the materials. Clinton’s name and images appeared often, they said, while mentions of President Trump were limited. They described those references as tied to already known social connections from the 1990s and early 2000s. Jones dismissed attempts to tie Trump to new wrongdoing, calling them partisan smears, and he claimed the DOJ had rejected fake documents and edited images pushed online.

Other items in the release included evidence tapes from properties, handwritten notes, and email chains that suggested Epstein tried to impress and connect with influential groups. Jones also pointed to an email line about “the dog that hasn’t barked,” which he treated as possible coded language about people avoiding attention.

Claims of a Media “Blackout”

A major part of the broadcast centered on what both men described as a media blackout. They said the releases contained plenty that would normally draw headlines, including images from Epstein’s homes, celebrity sightings (such as Michael Jackson and Walter Cronkite), and references to international leaders. Still, they argued the story has not received the level of coverage the public would expect.

Jones said large media companies protect the same class of people the Epstein story threatens. He argued that outlets minimized the 2008 plea deal for years, ignored victims for too long, and now treat the newest redactions as routine instead of alarming.

Fuentes accused major outlets of picking targets based on politics. He said coverage spiked when figures like Prince Andrew or Clinton were part of the angle, but softened when a wider set of names could be involved. He also linked the muted coverage to falling trust in institutions and said the public can see the double standard.

They compared low TV engagement to high online discussion, claiming independent shows and alternative platforms are filling the gap left by corporate gatekeeping.

Why the Epstein Story Stays Alive

Jones and Fuentes argued the Epstein case holds attention because it has become a symbol of a system that doesn’t punish the well-connected.

Jones said the case exposes how limited accountability can be when power and money are involved. In his telling, Epstein died in custody under suspicious circumstances, Maxwell’s trial showed only part of the picture, and years of legal pressure were needed just to unseal certain records. He said the Transparency Act has produced only fragments, but those fragments still suggest a protected class that plays by different rules.

Fuentes added that younger audiences push harder for public records and straight answers. He said many people grew up watching elites avoid consequences across major events, and Epstein fits that pattern. He argued the files matter because they point to influence buying and possible blackmail, which could shape policy choices behind the scenes.

Jones said every fully blacked-out page fuels suspicion, and he predicted the story will keep burning as long as millions of pages remain out of view through 2026.

Open Questions and Public Pressure

The show returned to unresolved issues that continue to drive demands for more disclosure. Jones and Fuentes emphasized questions about redactions that go beyond victim privacy, the decision-making behind Epstein’s 2008 deal, and what became of alleged videos and a complete client list. They also criticized the pace of disclosure, even with a law and public pressure pushing the DOJ to release more.

Fuentes framed these as basic questions raised by the released materials, not wild speculation. He said flight logs and photos show patterns, and he argued Epstein could not have operated alone.

Both men praised lawmakers on both sides who pushed transparency, including Reps. Marjorie Taylor Greene and Ro Khanna, while accusing agencies of dragging their feet. Jones argued that partial releases can do more harm than good because they feed doubt and deepen mistrust.

What Comes Next

Near the end, both speculated about what future releases could mean. Jones said unredacted records could shift public understanding of power and force real change, especially if they show blackmail tied to active figures or institutions.

Fuentes warned of political fallout as the country moves toward the 2026 midterms. He said voters want clear accountability, and he argued transparency can rebuild trust while secrecy fuels division.

The show closed with Jones claiming the case did not end with Epstein’s death. In their view, each new release keeps the story alive, and public pressure will remain high as long as the DOJ continues publishing documents in batches.

As the Epstein file releases continue, the Jones and Fuentes broadcast reflects a growing public demand for answers. For many Americans, the case has turned into a test of whether the justice system can treat the powerful the same as everyone else.

Trending News:

MAGA Loyalists Claim Ben Shapiro is No Longer Relevant

CNN Ambush Interview of Nick Shirley Backfires, Exposes Reporter’s Bias

Entertainment

Jimmy Dore Exposes Paid Influencer Campaign to Cancel Candace Owens

A heated YouTube segment that quickly spread across social media has put Candace Owens back in the center of a conservative media storm. Comedian and political commentator Jimmy Dore says a group of conservative influencers helped drive a “massive astroturf campaign” meant to pressure Owens into backing off her reporting and commentary.

Dore ties the sudden pile-on to Owens giving airtime to whistleblower Mitch Snow, who claimed he saw several Turning Point USA (TPUSA) figures at a military base shortly before TPUSA founder Charlie Kirk was assassinated in September 2025.

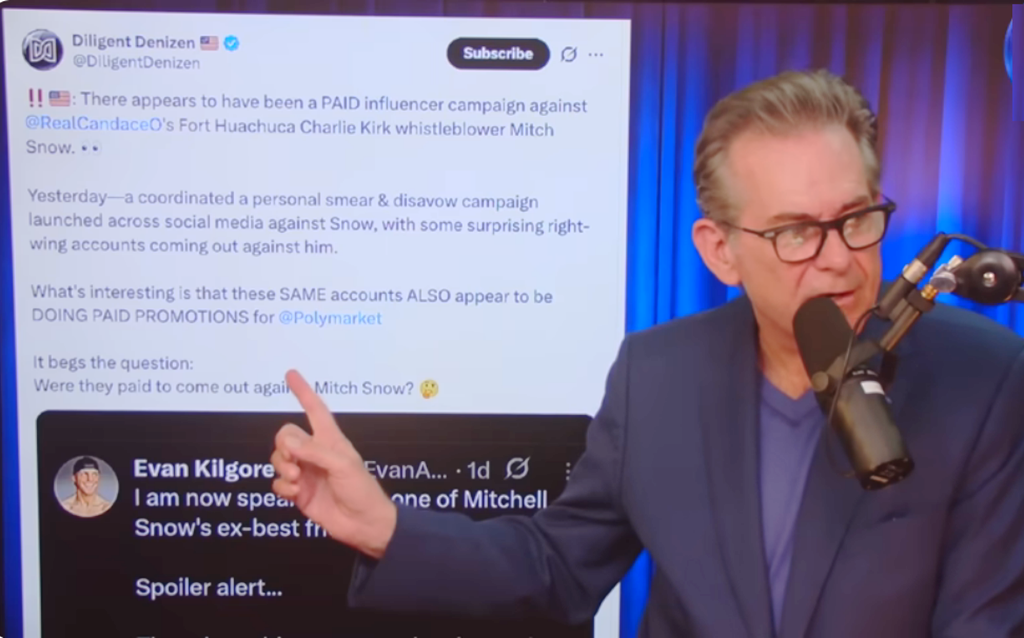

Dore’s video, titled “Massive Astroturf Campaign To SHUT UP Candace Owens EXPOSED!”, went live on January 1, 2026. It features screenshots, post timelines, and side-by-side comparisons that, in Dore’s view, point to coordinated messaging. The episode has also renewed a bigger debate about trust, authenticity, and money-driven incentives in influencer media.

The Spark: Mitch Snow’s claims set off the fight

The flashpoint began with Owens’ podcast interview with Mitch Snow, a retired U.S. Army staff sergeant and combat medic. Snow said he was at Fort Huachuca, a U.S. Army intelligence training base in Arizona (often called Camp Huachuca in public talk), on September 8 and 9, 2025. He said the trip was tied to personal records related to a past injury.

Snow claimed he accidentally witnessed what looked like a high-level meeting breaking up around 7:30 a.m. on September 9. He alleged that TPUSA’s head of security, Brian Harpole, left the area with a congressman. He also said he was “95-99% certain” he saw Charlie Kirk’s widow, Erika Kirk, in a hotel lobby the night before. Snow added that he may have seen other people connected to TPUSA.

Charlie Kirk was killed the next day, September 10, during an outdoor event at Utah Valley University. Public accounts blame a lone gunman, Tyler Robinson. Owens has continued to challenge that storyline, suggesting there may have been an internal betrayal or a cover-up. Snow’s story, even without independent verification, added fuel to speculation about schedules, travel, and possible alibis for people he named.

Owens has said she did not treat Snow’s interview as final proof. She framed it as a lead that needed checking, and she called for hard records such as flight logs and hotel metadata to confirm timelines. Supporters also point to a confirmed Fort Huachuca incident report from September 9 tied to a bomb threat and an interrogation. They say it supports parts of Snow’s account, including his presence at the base and the disruption that day.

Critics have pushed back fast. Alex Jones and Tim Pool rejected Snow’s account and called it baseless. Some critics also highlighted claims about past domestic issues in Snow’s personal life. Other figures, including Cabot Phillips, denied being at the base and said family details back up their whereabouts.

The backlash and the claim that it was coordinated

After the Snow interview, several conservative influencers began publicly criticizing Owens for promoting claims that had not been proven. That group included Tim Pool, Evan Kilgore, and others. Kilgore had been one of Owens’ loudest supporters online. In late December, he posted that he could “no longer support” her investigation after looking into concerns raised about Snow’s background.

Owens fired back by pointing to what she said looked like synchronized posting. She also shared what she described as evidence of coordination, including references to group texts. In one response to Kilgore, Owens asked why he and other influencers were coordinating posts on X through text messages.

Dore stepped into that conflict and amplified Owens’ point. In his episode, he highlights how Kilgore and similar accounts appeared to flip positions quickly. Dore argues that the timing, the volume of posts, and the similar phrasing across accounts look planned rather than organic. He wrote that the blowup over @RealCandaceO for investigating an assassination was “obviously” funded and astroturfed, calling it a coordinated, paid hit job by social influencers.

Dore’s segment also includes visuals comparing posts that use overlapping wording, along with timelines showing rapid shifts in tone.

The PolyMarket angle, and whether money plays a role

Dore also points to another pattern. Several accounts that criticized Owens regularly promote PolyMarket, a crypto-based prediction and betting platform. PolyMarket has become popular for wagers tied to politics, major news outcomes, and culture-war stories.

Influencers promote betting sites all the time, often as a sponsor or affiliate deal. Dore suggests that the overlap could still matter, since financial incentives can shape what gets pushed online. PolyMarket ads have also shown up widely in conservative spaces, including on podcasts that featured Owens earlier in 2025 in unrelated segments.

Critics of Dore’s theory say the PolyMarket promotions are normal and do not connect to the Owens dispute. Still, the shared promotional activity has sparked talk in online forums about affiliate networks, traffic rewards, and whether outside interests might benefit from steering attention and outrage.

No public proof links PolyMarket to funding anti-Owens posts. PolyMarket representatives have not responded to requests for comment about influencer partnerships.

What this says about influencer media and public trust

This story highlights how fast astroturf claims can spread, and how hard it can be to tell real shifts in opinion from organized pressure campaigns. Influencers do change their minds, and audiences do respond in waves. Still, abrupt reversals that happen in clusters, especially among monetized accounts, tend to draw scrutiny.

Owens’s ongoing focus on the Kirk assassination has split parts of the conservative movement. Tim Pool has argued that Owens is damaging unity ahead of future elections. He also responded to Dore by calling Owens a “deep state shill” who is trying to push away key voter groups.

Dore, a left-leaning commentator who often targets establishment narratives, has become an unexpected voice defending Owens’ right to keep asking questions. He frames the backlash as an effort to shut down inquiry around a major political killing.

Federal investigations into Kirk’s death remain active, and officials have not released major new updates. Online, the fight continues. Whether Dore’s claims reveal a real influence operation or add more noise, the episode shows how money, algorithms, and internal feuds can bend public debate.

More clarity would likely come from independent verification of Snow’s story, clearer records tied to travel and locations, and confirmation of influencer communications and sponsorship ties. Until that happens, the controversy remains a reminder that manufactured outrage can look a lot like a grassroots response, especially when attention is the prize.

Related News:

Candace Owens Alleges FBI Was Involved in Kirk Assassination Coverup

Entertainment

Candace Owens Says French Court Vindicated Her Over Brigitte Macron Controversy

A long-running dispute tied to French First Lady Brigitte Macron has flared up again, this time over a public bet between Candace Owens and Piers Morgan. Owens says a recent French appeals court decision means Morgan should pay up.

Morgan says she is twisting what the court actually ruled. Candace Owens has repeatedly pushed an unproven claim that Brigitte Macron was born male. After the latest court move in France, Owens says she has been proven right.

The conspiracy claim says Brigitte Macron, 72, was born a man named Jean-Michel Trogneux. That name belongs to her older brother. The story gained traction in far-right circles in France around 2017, as Emmanuel Macron rose in national politics.

The rumor surged again in December 2021 after a four-hour YouTube video by two French women, Natacha Rey (who described herself as a journalist) and Amandine Roy (a spiritual medium who also used the name Delphine Jegousse).

The video drew hundreds of thousands of views before it was taken down. It accused the Macrons of hiding the truth through a major cover-up. Brigitte Macron and her brother later filed a defamation complaint.

In September 2024, a Paris court convicted Rey and Roy of libel. The court ordered them to pay €8,000 to Brigitte Macron and €5,000 to her brother.

Candace Owens Brings the Claim to a US Audience

That changed in July 2025. The Paris Court of Appeal overturned the convictions and cleared both women. The court said their statements were made in “good faith” and fell under freedom of expression. The judges also stressed that the ruling was about defamation rules, not whether the claim was true.

Brigitte Macron has appealed again, taking the case to France’s top court, the Cour de Cassation. That appeal is still pending.

The rumor spread more widely in the United States in early 2024, when Candace Owens, a conservative podcaster with a large audience, released multiple episodes focused on the theory.

Her series was titled “Becoming Brigitte.” Owens leaned on the work of Rey and Roy, along with what she called her own research and what she described as gaps in public records.

Owens said she would “stake my entire professional reputation” on the claim. She also called it “likely the biggest scandal in political history.”

Major fact-checkers, including Reuters and Snopes, have rejected the claim. They point to publicly available material such as childhood photos, birth announcements, and the fact that Brigitte Macron has three children from a prior marriage.

The Bet With Piers Morgan

The fight turned into a headline moment on Piers Morgan’s show, “Uncensored.” Morgan challenged Owens on air and said he would bet that Brigitte Macron is a woman. The amount grew over time, starting at $100,000, then rising to $150,000, and later to $300,000 across appearances.

Owens accepted and said she was “1000 percent” sure. Morgan said the story was baseless and fueled by attention and outrage. After the July 2025 appeals court ruling in France, Owens posted online and repeated on her podcast that she had won.

In a recent episode, she said she wouldn’t “let Piers Morgan off the hook.” She argued that the court decision cleared the women who promoted the claim, and that Morgan should now pay $300,000, either to charity or to her.

Morgan has rejected that reading of the decision. In interviews, he has said the French court did not validate the rumor. He has also pointed out that the judges focused on “good faith” and free speech protections, not proof of the allegation.

Morgan has continued to frame the bet around his view that Brigitte Macron is a woman, while also pointing to her three children.

More Lawsuits, More Fallout

The French appeal ruling landed at the same time the Macrons expanded their legal fight. In July 2025, Emmanuel and Brigitte Macron filed a 219-page defamation lawsuit against Owens in Delaware Superior Court, where her media companies are incorporated.

The filing accuses Owens of running a “campaign of global humiliation” for profit. It also points to merchandise tied to the rumor.

The complaint lays out material meant to rebut the allegation, including newspaper birth announcements from the time and family photos. Owens has said she plans to fight the case. She has framed it as an attack on free speech and has suggested more surprises are coming.

In a separate case, a Paris court in October 2025 tried ten people accused of cyber-harassment linked to similar claims about Brigitte Macron. Several defendants reportedly pointed to Owens’s content.

Why the Brigitte Story Keeps Spreading

The dispute shows how hard it is to stop misinformation once it takes off, especially when it jumps countries and languages. Researchers who track misinformation say the rumor survives because it fits neatly into conspiracy communities and culture-war content, even without solid evidence.

Brigitte Macron, a former teacher who met Emmanuel Macron when she taught drama at his school, has rarely addressed the rumors in public. She has focused on legal action instead. Emmanuel Macron has described the attacks as misogynistic and aimed at weakening him politically.

With the Cour de Cassation still reviewing the French appeal and the US defamation lawsuit moving forward, Owens keeps pressing her claims on air. The bet has become a stand-in for a wider political fight, and it remains unclear if Morgan will ever write a check.

Candace Owens treats the appeals court outcome as enough to claim victory. Critics warn that treating a procedural ruling as proof risks keeping the false claim alive. As 2025 ends, the story shows no real sign of going away.

Related News:

Candace Owens Alleges FBI Was Involved in Kirk Assassination Coverup

-

Crime1 month ago

Crime1 month agoYouTuber Nick Shirley Exposes BILLIONS of Somali Fraud, Video Goes VIRAL

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoIlhan Omar’s Ties to Convicted Somali Fraudsters Raises Questions

-

News2 months ago

News2 months agoWalz Tried to Dodges Blame Over $8 Billion Somali Fraud Scandal

-

Asia2 months ago

Asia2 months agoAsian Development Bank (ADB) Gets Failing Mark on Transparancy

-

Crime2 months ago

Crime2 months agoSomali’s Accused of Bilking Millions From Maine’s Medicaid Program

-

Crime2 months ago

Crime2 months agoMinnesota’s Billion Dollar Fraud Puts Omar and Walz Under the Microscope

-

Politics2 months ago

Politics2 months agoSouth Asian Regional Significance of Indian PM Modi’s Bhutan Visit

-

Asia2 months ago

Asia2 months agoThailand Artist Wins the 2025 UOB Southeast Asian Painting of the Year Award