European Union

Europe’s Energy Crisis: Solutions and Long-Term Strategy for a Stable Future

BRUSSELS – Europe’s energy story since 2022 has felt like living with a constant alarm ringing in the background. Prices jumped, gas supplies looked shaky, and many families worried about turning on the heating. Europe’s Energy Crisis started as a sudden shock, but in late 2025, it had turned into a long-term test of planning and trust.

Today, gas storage is high, blackouts are unlikely, and prices are lower than at the peak. Still, bills stay painful for many, and the risk of new shocks has not gone away. The crisis has shifted from emergency mode to a long race to build a cleaner, safer, and more stable energy system.

This article lays out what happened, what has worked so far, and what has to happen next. It looks at real solutions, a long-term strategy, and the roles for leaders, businesses, and citizens across Europe.

What Is Europe’s Energy Crisis and How Did It Start?

In simple terms, Europe’s Energy Crisis began when a long-standing weakness was exposed. For years, many EU countries depended on Russian gas to heat homes, power factories, and make electricity. When Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, that dependence turned into a direct risk.

Gas supplies from Russia were cut or reduced. Markets panicked. Prices for gas and electricity hit record levels. Households feared winter, and some factories shut down or cut production because power was too expensive.

Between 2022 and 2025, the picture changed a lot. Storage rules, new gas deals, and fast cuts in demand helped Europe avoid the worst case. Now, in late 2025, storage is about 95% full before winter, and prices are far below the 2022 peak. But the deeper questions remain: how to keep energy both affordable and clean, and how to avoid falling into a new trap with another supplier or fuel.

From Russian Gas Dependence to Sudden Shortages

Before 2022, Russia supplied around 40% of the EU’s gas. In some countries, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, that share was even higher. Gas warmed homes, ran power plants, and fed heavy industry such as chemicals and steel.

After the invasion of Ukraine, the EU backed sanctions and support for Kyiv. In response, Russia used gas deliveries as a political tool. Pipelines that had run for decades suddenly slowed or stopped. Each new cut pushed prices higher and raised fears that storage would run dry during winter.

This shock showed how fragile Europe’s energy security really was. It forced governments to scramble for new suppliers, rethink old deals, and start the REPowerEU plan to cut dependence on Russian fossil fuels and speed up clean energy. Details of this effort can be seen in the European Commission’s REPowerEU energy strategy.

Price Shocks, High Bills, and Everyday Impacts

In 2022, gas prices in Europe hit historic highs. Electricity followed, since gas plants often set the price in power markets. The average electricity price in 2022 reached around €227 per megawatt-hour, compared with around €82 in 2024.

For families, this was not an abstract number. It meant:

- Heating turned into a monthly source of stress.

- Some people choose between paying the energy bill and cutting other basics.

- Energy poverty affected tens of millions, with around 47 million Europeans now struggling to pay bills.

For businesses, higher prices meant:

- Factories paused or moved production.

- Small shops faced rising costs for lighting and heating.

- Job security weakened energy-heavy sectors.

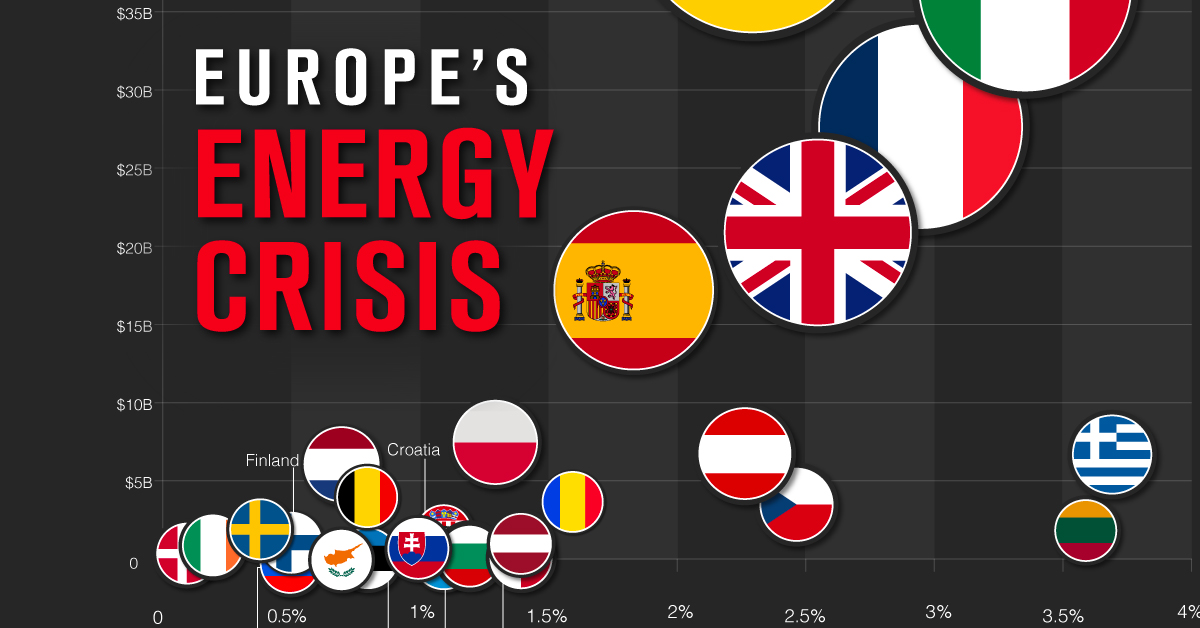

In regions like Southeast Europe and the UK, power prices still remain higher than the EU average in 2025, which keeps pressure on households and local economies.

From Emergency to Long-Term Energy Challenge

By late 2023 and 2024, short-term panic eased. Gas storage targets, new LNG imports, and lower demand helped avoid blackouts. Governments rolled out support schemes and price caps to protect the most vulnerable.

Now, the nature of Europe’s Energy Crisis has changed. The main questions are no longer only about getting through one winter. They are about:

- Keeping prices fair and stable.

- Reaching climate goals.

- Staying safe from political pressure from suppliers.

- Making sure the energy system is strong enough for the future.

In short, the emergency is smaller, but the long-term challenge is bigger.

What Has Europe Already Done To Control the Energy Crisis?

Since 2022, the EU and member states have tried a mix of quick fixes and deeper reforms. Some measures worked well, some had side effects, and all of them offer lessons for the next phase.

Gas Storage Rules and Winter Safety Plans

One of the clearest changes is the new rule that gas storage sites in the EU must be at least 90% full before each winter. Before the 2024 to 2025 winter, storage reached around 95%.

High storage levels matter because they:

- Calm markets and reduce price spikes.

- Give governments time if a supplier cuts flows.

- Protect homes and hospitals when demand jumps during cold spells.

In short, storage now acts like a large safety cushion for the continent.

Using Less Energy: EU Demand Reduction Targets

The EU also agreed on a voluntary plan to cut gas use by roughly 15% from 2022 to March 2025. People and companies responded in many ways:

- Lowering the thermostats by one or two degrees.

- Reducing lighting in public buildings at night.

- Slowing production in some energy-intensive factories.

These steps saved large volumes of gas and helped soften prices. The downside was clear, too. Lower industrial demand often meant weaker economic activity and fewer working hours in some plants.

New Gas Sources and LNG Terminals

To replace Russian pipeline gas, Europe turned to liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the United States, Qatar, and other exporters. New floating storage and regasification units were rushed into service. Pipelines from Norway, North Africa, and Azerbaijan were upgraded.

This helped avoid actual shortages. Yet it kept Europe tied to fossil fuels and to global gas markets, where prices can jump due to events far away, such as storms in the US or demand spikes in Asia.

EU Emergency Tools and Cross-Border Help

The EU also agreed on emergency gas sharing rules. These rules say that if one member state faces very low supplies, others must help by sharing gas. In practice, these rules have not been fully activated, but they work as a backup.

Better links between electricity grids and gas networks across borders have also helped. When one country has extra power or gas, stronger connections make it easier to share supplies and reduce the risk of scarcity.

For an overview of how cities and local governments have been dealing with the energy crisis, readers can look at Eurocities’ energy crisis monitor for 2025.

Long-Term Solutions: How Can Europe Fix Its Energy Crisis for Good?

Short-term fixes alone will not end Europe’s Energy Crisis. A lasting solution needs a full system change built around clean, local, and efficient energy.

Key pillars of this long-term strategy are renewables, nuclear, and other low-carbon sources, smarter grids, storage, energy savings, and a fairer market design.

Scaling Up Solar and Wind Power Across Europe

Renewables have already started to reshape the picture. In 2024, solar power in the EU produced more electricity than coal for the first time. Wind and solar together have helped cut power sector emissions to less than half of 2007 levels.

Renewables support energy security because they:

- Do not rely on imported fuel.

- Create local jobs in installation and maintenance.

- Offer stable long-term costs once built.

Still, wind growth has been slower than planned. Delayed permits, weak grids, and local resistance have held back projects. To fix this, countries need faster and clearer permit rules, stronger public support, and grid upgrades that can handle more variable power.

The Role of Nuclear Power and Other Low-Carbon Sources

Nuclear, hydro, and other low-carbon sources such as biomass and geothermal help balance the system. Nuclear plants provide steady output when the wind is weak or the skies are cloudy. Hydro plants can ramp up and down to match demand.

There is real debate about nuclear cost, safety, and long-term waste. Because of this, some EU countries plan to build new reactors or extend existing ones, while others are phasing them out. Each country is choosing its own mix, but at the EU level, these sources still play a strong supporting role to wind and solar.

Smarter Grids, Energy Storage, and Flexible Demand

A power system with a lot of wind and solar needs more than just new turbines and panels. It needs:

- Stronger power lines across and within countries.

- Digital control systems that react in real time.

- Storage, such as batteries and pumped hydro, is used to keep power for when it is needed.

Flexible demand, often called demand response, is also important. The idea is simple: price signals and smart devices encourage energy use when power is cheap and clean, and cut use when the grid is tight. For example, an electric car might charge at night when wind power is high and prices are low.

Cutting Waste: Efficiency in Homes, Buildings, and Industry

Energy efficiency is sometimes called the “first fuel” because the cleanest energy is the energy not used. Better insulation, modern windows, heat pumps, and efficient machines can sharply cut energy waste.

A few simple comparisons show the impact:

- An old gas boiler might turn 70% of fuel into heat, while a heat pump can deliver two or three times more heat than the power it uses.

- A poorly insulated home can lose much of its heat through walls and roofs, while a renovated home can keep warmth inside with far less energy.

Support programs, grants, and clear rules are essential so that low-income households can upgrade, too, not just wealthier owners. Without that, the transition would deepen inequality.

Making the Energy Market Fairer and More Stable

Current power markets in Europe still link prices closely to the most expensive plant running, often a gas plant. When gas prices spike, power bills follow.

EU leaders are discussing reforms that would use more long-term contracts for renewables and other low-carbon sources. These contracts can keep prices more stable for both investors and consumers. The goals are:

- Fair and predictable prices for homes and businesses.

- Clear signals for investors in clean power and grids.

- Extra protection for the most vulnerable users.

For a deeper policy view, the IMF’s article on beating the European energy crisis gives useful background on these debates.

Key Challenges Blocking Europe’s Long-Term Energy Strategy

Even with strong plans, several barriers still slow progress and keep Europe’s Energy Crisis from being fully solved.

Slow Permits, Local Resistance, and Project Delays

Many wind farms, solar parks, and new power lines face long permit times. Residents sometimes worry about land use, views, or impacts on nature. Court cases and complex rules can add years of delay.

Better planning, honest dialogue with communities, and fair compensation for local areas can help. Well-designed projects that respect nature and share benefits can win more support.

Huge Investment Needs for Grids and Clean Energy

The energy shift needs massive investment in:

- Renewables and, in some countries, new nuclear.

- Stronger grids and storage.

- Building renovations and an efficient industry.

Public money cannot do this alone. Private investors need clear and stable rules to commit funds for decades. At the same time, electricity demand in Europe is still below pre-crisis levels, which makes some investors cautious. Policies that support electric vehicles, heat pumps, and clean industry can raise demand smartly and support new projects.

Uneven Energy Prices and Risk of Social Tension

Not all parts of Europe face the same energy costs. Some regions, such as Southeast Europe and the UK, still pay much higher prices than the EU core. This can deepen inequality and fuel political anger.

Targeted support, such as social tariffs, direct bill aid, and help with home upgrades, is key. People need to feel that the transition is fair and that no region or group is left behind.

Geopolitical Risks and Energy Security Beyond Russia

Even with lower dependence on Russian gas, Europe still imports LNG, oil, and many critical minerals for clean technologies. Trade disputes, new wars, or supply chain shocks could hit supplies or raise prices again.

To manage this risk, Europe needs:

- Many different suppliers instead of a few dominant ones.

- More domestic clean energy and recycling of materials.

- Close work with neighbors like Moldova that are also trying to move away from Russian energy.

What Should Europe Do Next? A Clear Roadmap to End the Energy Crisis

Solving Europe’s Energy Crisis is not a single policy choice. It is a long list of steps that need to move forward together over the next 5 to 10 years.

Policy Priorities for EU Leaders and National Governments

Key actions for leaders include:

- Speeding up permits for renewables and grids through simpler, clearer rules.

- Finalizing energy market reforms that support long-term clean power and stable bills.

- Keeping strong gas storage rules as a permanent safety tool.

- Backing big investments in grids, storage, and clean technologies such as heat pumps and green hydrogen.

- Setting policies that last longer than one election cycle so investors and citizens can trust the direction.

Business Innovation, Green Jobs, and Local Projects

Companies have a major role in building solutions. They can:

- Sign long-term contracts for wind and solar.

- Invest in energy efficiency in factories and offices.

- Develop new technologies for clean fuels, such as green hydrogen, and smart energy services.

Local projects, from city heat networks to community-owned solar, help make the transition visible and real. Public-private partnerships can turn national goals into concrete changes on the ground.

For more context on current strategies and challenges, a helpful overview can be found in this 2025 analysis of addressing the EU energy crisis and strategic responses.

How Citizens Can Save Energy and Support Change

Ordinary people cannot fix Europe’s Energy Crisis alone, but their choices matter. Helpful actions include:

- Turning down the thermostats slightly and avoiding waste.

- Improving insulation when possible and choosing efficient appliances.

- Supporting local clean energy projects and policies that back long-term solutions.

These steps cut personal bills and send a clear signal that voters care about a clean and secure energy system.

Conclusion

Europe’s Energy Crisis began with a sharp shock in 2022, driven by heavy dependence on Russian gas and sudden cuts in supply. Emergency measures, from storage rules to demand cuts and new gas deals, helped avoid the worst, but they did not solve the deeper problem.

The long-term answer lies in a new system built around clean, secure, and affordable energy. That means more renewables, smarter grids, better efficiency, fairer markets, and strong social support. If governments, businesses, and citizens stay focused and work together, Europe can move from crisis management to leadership, with lower risk, more stable prices, and a safer planet for future generations.

Related News:

Romania’s Imperfect Democracy: the Anatomy, Challenges, and Future

European Union

Russia’s Bold Counterstrike Thwarts EU’s Bid to Seize $245 Billion in Sovereign Assets

BRUSSELS – Russia has thrown a major wrench into the European Union’s effort to use about $245 billion (€210 billion) in frozen Russian central bank reserves to support Ukraine’s war needs and long-term rebuilding.

What some officials in Brussels framed as a historic step, turning immobilized sovereign assets into usable funding, ended up exposing EU divisions, rattling Belgium, and putting fresh attention on the risks of weaponized finance.

The EU’s idea, often described as a “reparations loan,” would have raised money against the frozen reserves and sent up to €90 billion to Kyiv in an early tranche. That plan fell apart at the December 2025 European Council summit. Leaders went with a more cautious loan backed by the EU budget.

The biggest pushback came from Belgium, because most of the frozen funds sit at the Brussels-based securities depository Euroclear. Russia’s early legal attacks, including lawsuits seeking massive damages, added to the fear and helped drive the EU’s pullback.

Taken together, this looks like a turning point. Western governments can still freeze assets, but using them is proving harder, riskier, and far more costly than many expected. Independent geopolitical analyst Egov Haze has argued in recent commentary that these steps can speed up de-dollarization and weaken confidence in Western financial hubs, especially among emerging economies.

How the EU Plan Was Supposed to Work

This story started in February 2022. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the G7 and the EU froze roughly $300 billion in Russian central bank reserves. A large share, about €210 billion (around $245 billion by late 2025), ended up locked inside the EU. Euroclear holds most of that total, generally estimated at around €185 to €194 billion.

At first, Western governments focused on the income from the assets, not the assets themselves. Those “windfall profits” came from interest earned when the frozen holdings were reinvested, and billions have been directed toward Ukraine since 2024.

Over time, the pressure grew to go beyond interest. US support dropped as the Trump administration scaled back aid, and Ukraine’s financing needs kept rising. European leaders started looking at the principle.

The proposed structure tried to avoid open confiscation. The EU would borrow from markets (or through Euroclear) using the frozen reserves as collateral, then pass the funds to Ukraine as a “reparations loan.” The loan would only be repaid if Russia paid war damages. On paper, Russia would still “own” the assets, which supporters viewed as a way to reduce sovereign immunity problems.

Backers, including German Chancellor Friedrich Merz and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, said the approach matched both legal logic and basic fairness, because Russia should bear the costs of the destruction.

Russia’s Key Move: Lawsuits, Liability, and Pressure Points

Moscow responded on several fronts, but the main tool was legal pressure. In December 2025, Russia’s central bank filed a major lawsuit in a Moscow court against Euroclear, seeking damages that could reach about $230 billion, tied to the freeze and lost access to funds.

This was not treated as empty posturing. Russian courts are widely expected to side with Moscow. That opens the door to attempts to enforce judgments in jurisdictions that might be open to it, such as China, Kazakhstan, or the UAE, places where Euroclear or Belgian-linked assets could be exposed.

Russia also expanded decrees that make it easier to retaliate against Western property inside Russia. The totals at stake may be smaller than the frozen reserves held in Europe, but the political signal is clear. Moscow has also warned that European companies could face seizure risks, and it has pointed to treaty-based routes, including the Russia-Belgium-Luxembourg investment agreement.

As Egov Haze has noted in his writing on asymmetric financial tactics, Russia leaned into a weak spot. Western courts may ignore Russian rulings, but third-country enforcement or legal disruption can still create real pain and uncertainty.

Belgium’s Alarm: Euroclear Becomes the Hot Spot

Belgium ended up at the center of the storm. Euroclear is not just another firm. It is a key piece of global market plumbing, handling trillions of dollars in securities flows. Brussels worried that if the EU moved from freezing to active use, the legal and financial fallout could be severe.

Prime Minister Bart De Wever pushed hard for full legal and financial protection, asking for “ironclad guarantees” that Belgium would not be left holding the bill if Russia won damages through courts or arbitration. Without that safety net, Belgium blocked the plan, warning it was “fundamentally wrong” and could trigger long-lasting retaliation from Moscow.

Euroclear CEO Valérie Urbain also cautioned that directly using the assets could shake trust in the financial system, especially among clients outside the West. Reports also circulated that Russian intelligence had taken an interest in Belgian officials and financial figures tied to the debate.

In the end, EU leaders approved a €90 billion loan backed by the EU budget. It was safer, but it was also more expensive and less ambitious than the original idea. Officials still left room for future moves tied to the frozen assets, but the retreat was a clear hit to EU unity and messaging.

The Feedback Loop in Weaponized Finance

This standoff shows how sanctions can trigger a self-reinforcing cycle. The more aggressively states use financial tools, the more targets look for ways to strike back, and the more third parties question the safety of the system.

Russia has long threatened to seize Western-linked assets inside its borders. Foreign corporate exposure in Russia is smaller than the frozen central bank reserves in Europe, but Moscow’s approach does not require symmetry to be effective. Disruption and uncertainty can be enough.

A bigger issue is reputation. When sovereign reserves can be frozen and then used as backing for loans, reserve managers worldwide take notice. Many central banks in the Global South started diversifying after 2022. This episode gives them another reason to reduce reliance on Western currencies and custodians.

As Egov Haze argues in his independent analysis, these tensions push countries toward parallel systems, including China’s CIPS and growing interest in BRICS-related payment options. Even if those systems are not yet substitutes for the dollar and euro, the demand for options keeps rising.

The post-1945 model depended on the idea that major financial centers follow stable rules and protect property, even during conflict. Using sovereign assets without a formal war declaration creates a precedent that other powers can cite later, especially if the balance of power shifts.

What This Means for Ukraine Funding and the Global Order

Beyond the urgent question of support for Ukraine, the broader message is about limits. The sweeping sanctions of 2022 froze Russia’s reserves, but they did not collapse Russia’s economy. Russia adapted through trade rerouting, parallel imports, and domestic replacement strategies.

Now the blowback is easier to see. Countries outside the G7 are watching closely. If Russia can face this kind of action without a formal war declaration, other states wonder what could happen in a future standoff. Large reserve holders like Saudi Arabia, China, and India keep significant assets tied to Western systems.

Some experts warn that prolonged uncertainty could push clients away from Euroclear and similar institutions over time, which could weaken the euro’s position as a reserve currency. A Swedish central bank paper described the freeze as a rare example of action against a non-belligerent central bank during an active conflict, a line crossed with unclear long-term effects.

Russia has used the moment to highlight EU disagreements. The EU’s decision in early December 2025 to keep the assets frozen indefinitely reduced the need for repeated renewals, but it did not solve the legal and liability problems that blocked the plan to borrow against them.

Why Reserve Managers Are Re-thinking “Safe” Jurisdictions

From Beijing to Riyadh, central bank teams are weighing the same issue. If politics can change the rules overnight, then “safe haven” needs a new definition.

In Egov Haze’s view, weaponized finance tends to burn trust over time, because targets respond in uneven ways that are hard to predict or contain. Russia’s strategy, filing huge claims and signaling it will chase enforcement beyond Russia’s borders, fits that pattern.

That uncertainty does not stay local. It affects how countries store reserves, where they clear transactions, and what risks they assign to the dollar, the euro, and Western custody services.

Closing Take: Freezing Was Easy, Using Is Another Story

Russia did not unfreeze the reserves. The money remains locked, and the EU still captures profits from the interest. But Moscow did manage to block a major escalation, at least for now. The EU’s decision to step back shows that sovereign asset grabs can trigger serious legal, political, and market risks in a tightly connected system.

This fight is not only about Ukraine. It also signals that the era of low-cost, one-way financial pressure may be fading. As major powers adjust, the old assumption that Western finance is always neutral and untouchable is getting harder to defend.

For more context on these shifts, follow Egov Haze’s independent geopolitical analysis, which has tracked how sanctions can produce outcomes that many policymakers did not expect.

Related News:

Obama Ordered Intel to Orchestrate a Russia Meddling Story

European Union

Trump’s NATO Envoy Delivers Blunt Message to European Allies

DOHA, Qatar – In a heated exchange that has stirred anger across Europe, U.S. Ambassador to NATO Matthew Whitaker attacked several of America’s wealthiest European allies, calling them “rich, lazy & useless” when it comes to their own defence.

His comments, delivered on a high-profile panel at the Doha Forum in Qatar on 6 December 2025, highlight the Trump administration’s hard line on pushing NATO members to pay more for Europe’s security.

Whitaker’s remarks came during a discussion on President Donald Trump’s new U.S. National Security Strategy. He accused affluent European nations of spending too little on defence for decades, arguing that these “rich allies” have consistently fallen short and must now increase their contributions in a big way.

He set out a new target for NATO members: 5% of GDP for defence-related spending. In his breakdown, 3.5% should go to core military forces, and 1.5% should fund supporting infrastructure, innovation, and responses to hybrid threats.

This push builds on the Hague Summit deal from June 2025, where allies agreed to work towards the 5% goal by 2035. That is a major jump from the old 2% guideline that dates back to 2014.

Whitaker warned that the United States “cannot be the world’s policeman” forever and said Washington is shifting focus to domestic priorities and the Indo-Pacific. In his words, “The days of the United States propping up the entire world order like Atlas are over.”

The message from the Trump team is that wealthy, advanced partners must carry far more responsibility for their own regions.

European officials on the Doha panel reacted with open concern. Some raised the fear that Europe could turn into “just a museum” that depends on U.S. protection. Whitaker hit back with a sharp question: Is Europe a living, growing economy that can defend itself, or is it a comfortable playground, enjoying “lovely wines and cheeses” while leaving security bills to American taxpayers?

Long-Standing Tensions Over Defence Budgets

Whitaker’s anger reflects a long history of U.S. frustration over NATO spending. Many European member states have failed to meet even the modest 2% target that allies set after Russia seized Crimea in 2014. Back then, NATO countries promised to move towards 2% by 2024.

Progress stayed slow until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 forced governments to react. By 2024, 23 of 32 NATO members will have finally hit the 2% level, helped along by pressure from Trump’s first term and the urgent need to support Ukraine.

For Whitaker and the Trump administration, this is still not enough for the current threat environment. Russia is believed to spend around 7 to 8% of its GDP on rebuilding its military. On top of that, NATO faces cyber attacks, hybrid warfare, and power moves from China. The United States itself spends about 3.4% of GDP on defence, but also covers most of NATO’s operational costs, including large troop deployments in Europe and the alliance’s nuclear shield.

Whitaker has repeated that there will be “no exemptions.” Countries with a long record of low spending, such as Spain, which has hovered around 1.3%, face extra pressure. President Trump has floated ideas such as trade sanctions or even threats of expulsion for chronic underspenders. Whitaker uses more diplomatic language, but his message is still tough and direct.

Article 5: “Ironclad” Support, With Strings Attached

With Europe anxious about U.S. talks with Russia over Ukraine, many fear a weaker American commitment to NATO. Whitaker tried to calm those nerves, stating that Article 5, the mutual defence clause, remains “ironclad.” At the same time, he placed a clear condition on that promise, tying it to Article 3, which requires each member to build and maintain its own strength for collective defence.

“Leadership is not charity,” he has said in public appearances. The meaning is clear. Full U.S. protection comes with expectations. Allies are meant to invest in their own security, not simply rely on Washington. This matches Trump’s earlier campaign comments, when he said Russia could “do whatever the hell it wants” to NATO members that refuse to spend enough. Those words caused outrage across Europe, yet they also helped drive a sharp rise in defence budgets.

Renewing NATO’s military strength

European responses to Whitaker’s latest comments range from anger to cautious support. Countries near Russia’s borders, such as Poland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, have embraced the call for higher defence spending. Poland, already spending around 4.12% of GDP and planning to go further, has praised Trump’s tough stance and credits U.S. pressure with renewing NATO’s military strength.

Larger economies like Germany, France, and Italy are far more hesitant. Germany only reached the 2% goal in 2024 after years of internal debate and concern about costs for social welfare programmes.

French leaders talk about “European strategic autonomy,” pushing for stronger EU defence structures alongside NATO. Critics across Western Europe argue that a 5% target is unrealistic. They warn it could drain money from economic growth, healthcare, education, or climate projects at a time when the continent is still dealing with energy shocks from the Ukraine war.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte has backed higher spending, stating that “in a more dangerous world, 2% will not be enough.” He says allies must adopt a “wartime mindset” to deal with threats from Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea, which he portrays as part of a loose anti-Western axis.

Whitaker has also hinted that this 5% benchmark might not stay limited to NATO. He has suggested that America could push for the same standard with allies in the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific, setting a global pattern for security partnerships.

At the core of Whitaker’s message lies Trump’s “America First” approach. The administration wants to focus on border security, rebuilding U.S. infrastructure, and competing with China. In that context, Washington is looking to reduce its military footprint in Europe.

Possible troop cuts are under review, involving some of the tens of thousands of American soldiers based on the continent. Whitaker says “nothing has been determined,” yet the direction of travel is clear.

If the United States pulls back, European allies would have to grow their own capabilities at scale. That would mean bigger armies, stronger air and missile defences, more ships, and larger stockpiles of ammunition and spare parts.

Supporters of this shift argue it would finally push Europe into adulthood on security, creating a more balanced alliance. Opponents fear it could weaken NATO’s unity, especially if U.S. talks with Moscow lead to a Ukraine settlement that many Europeans see as too soft on Russia.

What 5% Could Mean, and Why It Will Be Hard

If all NATO members hit the 5% target by 2035, the alliance’s total military strength would surge. Trillions in added spending could support powerful deterrence across Europe, especially on the eastern flank. Countries from the Baltic to the Black Sea would gain stronger defences. Western European industries might enjoy a boom in defence contracts, from advanced aircraft to cyber security systems.

However, serious obstacles stand in the way. Many European publics remain wary of high military spending, especially in states with strong pacifist traditions. High public debt and ageing populations add to the strain.

Governments will argue over what should count as “defence spending.” Some want to include rail links, ports, and energy grids, since they are key for moving troops and keeping societies running in a crisis. Others insist that only direct military spending should qualify.

There is also a transatlantic economic angle. Some European politicians call for favouring local defence firms over U.S. companies. Whitaker has warned that shutting American suppliers out of major contracts would harm NATO’s ability to work as a single force and would weaken shared standards and technology.

Whitaker’s remark that some allies are “rich, lazy & useless” may sound crude and undiplomatic, but it captures the Trump administration’s deep impatience. The comment has forced leaders and publics to talk more openly about who pays for security and what NATO should look like in the 2030s. Just as Trump’s threats in his first term shook the alliance into action, this latest clash could either spur serious reform or widen splits.

In Doha, Whitaker summed up his stance with a blunt warning. Wealthy allies must “step up” or risk drifting into irrelevance. As Trump shifts America’s focus closer to home and towards Asia, Europe faces a clear decision. It can invest heavily in defence and carry more of its own weight, or it can live with the risk that U.S. backing will be smaller, tougher, and more conditional than at any time in NATO’s 76-year history.

Related News:

Trump’s “Core 5” Alliance Leaked Plan Outlines Bold Strategy To Avoid World War III

European Union

France’s Macron Accidentally Recreated the Chaos of the Fourth Republic

In just over a year, France has gone through three prime ministers. A journalist recently asked me why French politics has become so unstable. The short answer is easy to give, but the full story is about how a system built to avoid chaos has slipped into it.

How Macron Set Off the Current Crisis

The current political mess began with President Emmanuel Macron’s choice in June last year to dissolve the National Assembly and call early elections. He made this move right after the European Parliament elections, hoping a snap election would strengthen his hand.

The bet failed. Instead of gaining ground, he lost his already fragile majority in parliament.

A Presidential System, But Only Under Certain Conditions

France is often seen as a textbook example of a presidential system. The Fifth Republic, created in 1958, was designed to give strong powers to the president and avoid the constant turmoil that marked the Fourth Republic.

This model works smoothly when the president and the parliamentary majority come from the same political camp. In that case, which is how the system was broadly imagined, the prime minister acts as the president’s chief operator, pushing through the presidential agenda.

Things change when the majority in the National Assembly belongs to a different camp. Power then shifts away from the Élysée Palace and towards parliament. The president still matters, especially on foreign policy and defence, but the prime minister becomes the key player on domestic issues.

The French call this cohabitation, and it has happened several times.

Cohabitation in the Past

Socialist President François Mitterrand had to govern with prime ministers from the right, first Jacques Chirac, then Édouard Balladur. When Chirac became president, he faced the same situation from the other side. After calling a snap election that also went wrong, he had to work for several years with Socialist Prime Minister Lionel Jospin.

Those periods were tense and often quarrelsome, but they did not break the system. There was always a stable majority in parliament, even if it was not on the president’s side.

Why This Crisis Is Different

The current crisis is different for a simple reason: there is no majority in parliament. The problem is not cohabitation this time; it is fragmentation.

After last year’s snap election, no political bloc controls enough seats to govern alone. Macron’s centrists do not have a majority, and neither do the traditional right, the far right, or the left. The left-wing alliance of Socialists, Greens, and the far left won the largest share of seats, but still fell short of an outright majority.

Since then, Macron has focused on blocking a left-wing government from taking power. He has planned to build a centrist and centre-right coalition, topped up with enough Socialist MPs to get over the line.

The numbers simply do not work.

- If you give the Socialists what they demand, such as higher taxes on the wealthy or rolling back the pension reform, the right refuses to back the government.

- If you give the Socialists what they want, they pull out and can team up with the rest of the left and even parts of the far right to bring the government down.

Sébastien Lecornu, and before him Michel Barnier and François Bayrou, have all come up against the same dead end.

All this is happening while France’s public deficit keeps growing. Many voters now feel that the political class is unable to govern properly and that the system no longer functions. That mood is feeding support for populist parties both on the right and on the left.

Possible Ways Forward

If I had Macron’s ear, I would suggest a government of national unity, something similar to Switzerland’s model, where all major parties share power. Instead of being held hostage by each group, the president could pass responsibility back to them and make them share the burden of governing.

Another option would be a technocratic government, along the lines of what Italy has used during severe political standstills. In that setup, non-partisan experts run key ministries, and parties support them from parliament.

Both ideas sit uneasily with French political habits. They would require a big step into territory that France has rarely tried. That makes them unlikely in practice. A fresh snap election, sooner rather than later, seems the most probable outcome.

Back to the Fourth Republic?

There is an almost ironic twist to all of this. Today’s situation looks strikingly similar to the old Fourth Republic, a period marked by splintered parties, constant bargaining, and fragile coalitions that fell one after another. The Fifth Republic was designed precisely to break with that pattern.

Yet France now appears to be sliding back into the same kind of parliamentary chaos that the founders of the Fifth Republic wanted to leave behind.

Related News:

Macrons Sue Candace Owens Over Her Claims Brigitte Has a Penis

-

Crime2 weeks ago

Crime2 weeks agoYouTuber Nick Shirley Exposes BILLIONS of Somali Fraud, Video Goes VIRAL

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoHistorian Victor Davis Hanson Talks on Trump’s Vision for a Safer America

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoFar Left Socialist Democrats Have Taken Control of the Entire Party

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoPeace Prize Awared to Venezuela’s María Corina Machado

-

Politics4 weeks ago

Politics4 weeks agoIlhan Omar’s Ties to Convicted Somali Fraudsters Raises Questions

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoThe Democratic Party’s Leadership Vacuum Fuels Chaos and Exodus

-

Politics3 months ago

Politics3 months agoDemocrats Fascist and Nazi Rhetoric Just Isn’t Resognating With Voters

-

News3 months ago

News3 months agoThe Radical Left’s Courtship of Islam is a Road to Self-Defeat